Patents, Dentists and Tortillas

When proprietary licensing intersects artmaking.

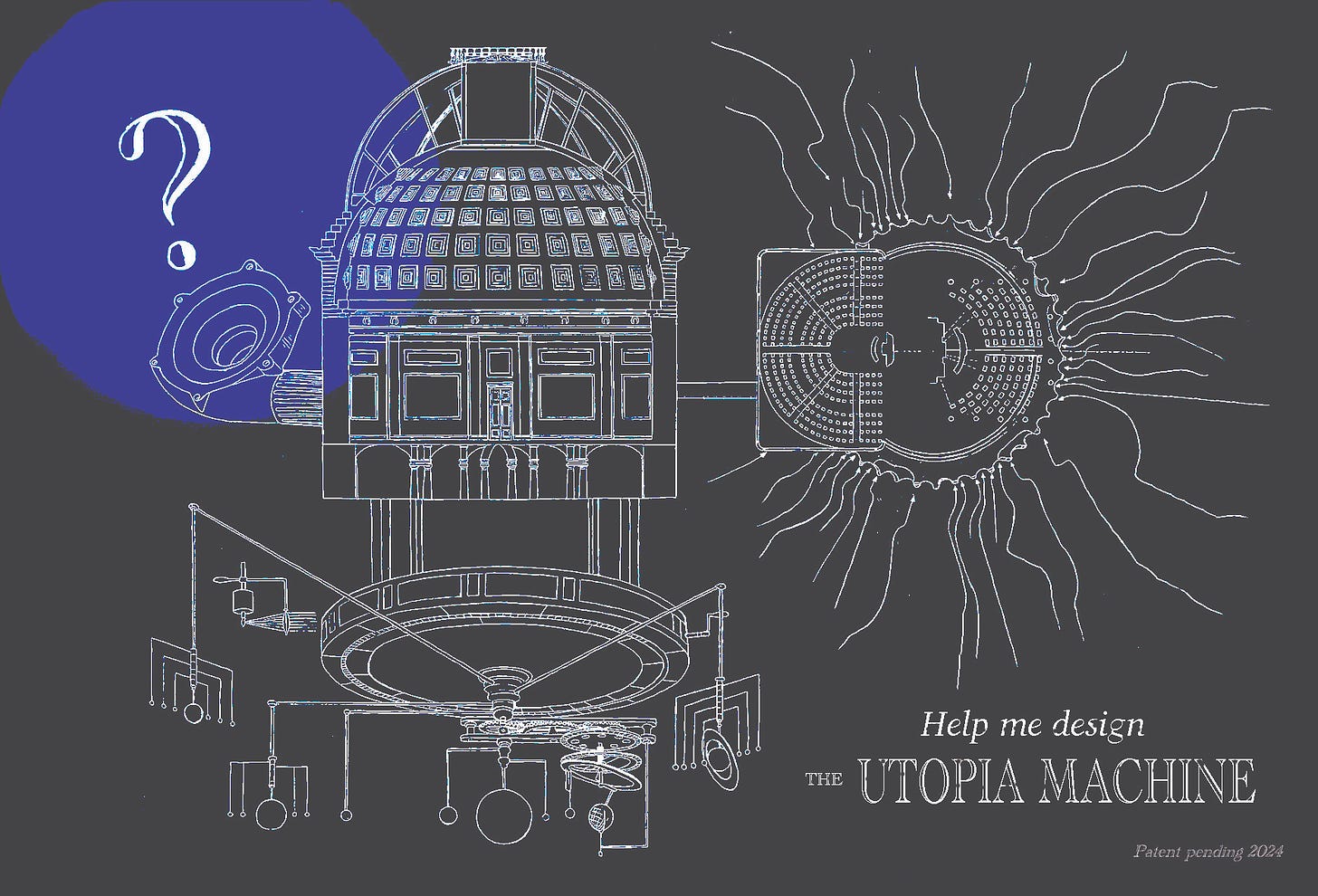

“Artists are inventors”, Ruby Lerner, the Founding Director of the Creative Capital Foundation told me once, arguing how contemporary art is ultimately about ideas that need sources of support. That self-evident, yet important, comment has remained with me over the years, mainly with the further question of how exactly art is inventing and inventing is art. Recently it came back to mind because the other day the great artist Ellen Harvey, who is a friend, sent out an email inviting proposals for future components that will integrate a “Utopia Machine”, for which she will create, in her words, “a huge fictional patent drawing”. The project is for an exhibition at the Los Angeles Central Library titled No Prior Art: Illustrations of Invention. For several months, Ellen has been studying and reviewing patent drawings, some of which recall a style of drafting out of Leonardo’s flying machines.

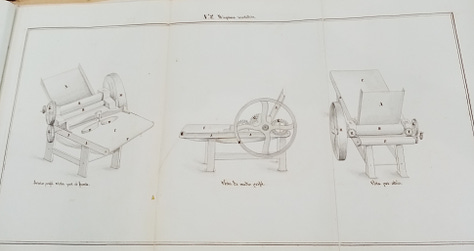

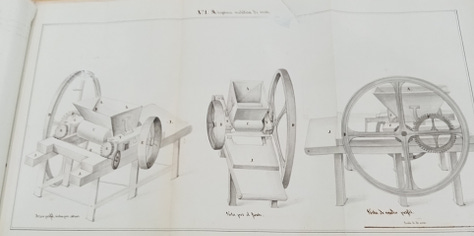

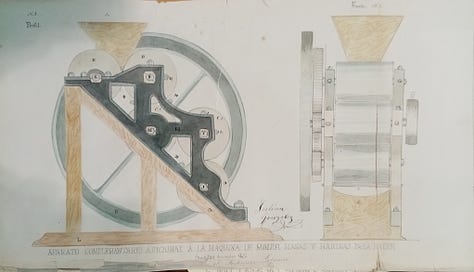

Ellen’s project personally resonates with me because my own family, the Helgueras, always had some kind of idealistic inventor bug. We always invented things, although seldom did they pan out successfully. My uncle, the sculptor Carlos Helguera, studied engineering and worked in a myriad of inventions, including a toilet flushing system. An automobile enthusiast, he was endlessly repairing and improving historic cars in a lot he had in the town of Lagos de Moreno, Jalisco. There, he also had a small factory (with only one employee) that produced a type of linen fiber using a giant turn-of-the-century machine. The fiber he produced was traditionally used for sealing pipes, but it was an antiquated method falling into disuse and for that reason his product was seldom in demand; he kept trying to find new uses for that fiber he was producing. I always admired his eternal optimism and inventiveness, even in old age. And a granduncle of mine, Andrés Helguera, was also an inventor, but never attained fame, wealth, or success. He, however, did create a promising invention: a tortilla warmer. He sought to address a common problem in Mexican everyday dining: the fact that warm corn tortillas are delicious the moment they come out of the comal (or from the tortillería if they are machine-made), but they get cold pretty quickly, even if they are wrapped in cloth. My granduncle’s device kept the tortillas warm and soft for hours. He designed a prototype and made an initial line that sold very well for a while, but for some reason he never reached the point of mass-production. We ended up with one at home which we used for decades very successfully, until it finally got lost during a move.

I asked Ellen whether she had any inventors in her family, to which she said: not really. “My mother’s family were farmers and my father’s family (the respectable ones) were coopers – barrel makers.” What drew her to the subject of patents was a Smithsonian residency at the American Art Museum where she visited the historic building once known as the “Temple of Invention,” a place where, for most of the 19th century, there was an exhibition hall where patent models and drawings of new inventions were exhibited every year. Known as a “museum of curiosities”, in its heyday had 100,000 annual visitors. There is an inherent optimistic American spirit in the notion of the “the citizen inventor”, as Ellen describes it: the democratic idea that anyone can come up with —and claim ownership of— an invention. This was legally codified when George Washington signed the Patent Act of 1790 (“the founding fathers were super excited about patents— It’s in Article 1 of the constitution”, Ellen points out). An American woman in the 19th century, even while unable to vote, could get a patent starting in 1809 (although would need to work through her husband to be able to benefit commercially from her invention). Thomas Jennings, the first known Black patentee (born free in New York) successfully patented a type of dry-cleaning method in 1821. Black women inventors did not manage to obtain patents until after the Civil War. Other later Black inventors include Sara Boone, who invented the morning ironing board in 1892, Alexander Miles, inventor of the automatic elevator doors in 1887, and Lewis Latimer, inventor of the carbon light bulb filament in 1881.

Ellen’s deadpan humor and insatiable curiosity shows in her interest in what she described to me as “the special room of shame” of failed patents at the old Temple of Invention, which I surmise were a bit of an inspiration to her Utopia Machine: an aspirational invention that brings together 100 or so ideas for making the world a better place.

The melancholia of the inventor is nonetheless worth pondering, if anything just in order to also behold the heroism, and anti-heroism, at times, inherent in the courageous adventure of creating new and useful things for the world. Various of these moving stories of inventors who got close to (but did not reach) success or were altogether forgotten is narrated by Paul Collins in his 2001 book Banvard’s Folly. These included Ephraim Wales Bull, who developed the renowned Concord grape in 1849 after many experiments with 22,000 different seeds. All his years of hard work in creating this beloved grape variety came to naught by the simple fact that every one of his grapes naturally had seeds that could be easily planted, grown, and reproduced, which made it impossible for him to control the profits generated by his own invention. Someone who benefitted from Bull’s grape was a New Jersey dentist named Dr. Thomas Bramwell Welch; he and his son first pasteurized the Concord grape juice in 1869. Bull’s gravestone reads: “he sowed; others reaped.”

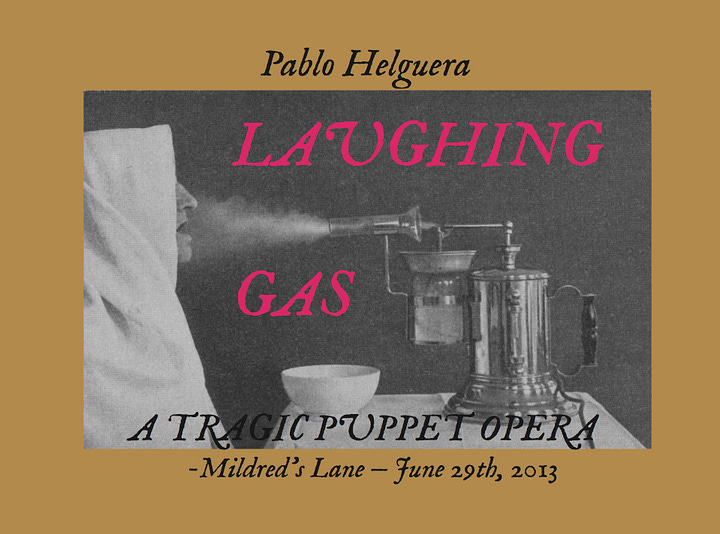

Speaking of dentists, another sad invention story is the one of Horace Wells, a 19th century Connecticut dentist who discovered anesthesia while observing the numbing effects of nitrous oxide, which was primarily used for entertainment at parties because it caused euphoria upon inhalation (thus its name of “laughing gas”). Because of a failed public demonstration of the effects of the gas on a patient during an extraction, Wells’s claim was dismissed; yet his former student and associate William Morton, knowing it was effective, sought to steal the ownership of the invention from Wells. Wells died destitute at a mental asylum at 33 years of age; Morton attempted through the rest of his life to claim the patent for anesthesia, especially when the Civil War came around and the US government simply used anesthesia for surgeries and amputations in the battlefield without even bothering to seek legal permission; Morton unsuccessfully sued the US government many times to seek remuneration for his research until his own death in a carriage accident. The tragic and convoluted story of this patent moved me to create a into a puppet opera on the subject in 2013, titled Laughing Gas.

Of course, copyright law is what protects artistic creations, and in some ways it is a much better protection than a patent (a patent license only lasts for about 20 years). But as we also know, copyright law is not very effective against works that are shameless imitation, but not outright forgery. There are many instances of imitators making works that are practically identical to those of better-known and original artists but leaving the latter ones unable to act legally on those imitations. I think of the Venezuelan conceptual artist Carlos Zerpa, who recently shared in social media that there is a copycat imitating a series of pieces that he started making more than a decade ago consisting in thousands of 33-rpm records threaded next to the other, creating giant snake-like sculptures. Copyright infringement aside (and given that this is not a case of copying an image per se but copying a method) presents the question of how artists can use the powers of patent law to protect their practice.

The answer seems to be that patent law comes in handy for artists, not to protect reproduction of their work but to protect a proprietary artistic process. Examples include the 2011 patent by Anish Kapoor for his non-reflective black pigment and Trevor Paglen’s 2018 patent for a device and method for tracking a classified satellite, which he has used in his works.

Sometimes these official patents have a debatable basis, such as the one that Salvador Dalí obtained in 1983 for his "method of stereoscopic representation of a three-dimensional image", also described as the "Dalí Stereoscopic Method”. More an example of artistic hubris, it might in any case be the closest example of an artistic style becoming patentable.

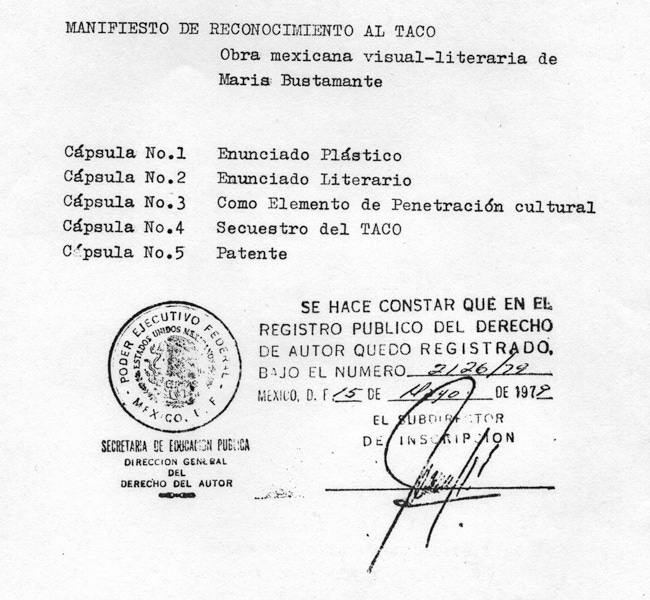

Of course, the patent process can become an artwork onto itself. Speaking of tortillas, in 1979 the Mexican feminist conceptual artist Maris Bustamante decided to patent the taco. Her argument to the federal patent office in Mexico was that the concept of the taco had never been claimed by anyone, so she was taking action. As I recall, according to Bustamante in her description of her patent application years ago, people in the bureau were puzzled, telling her “You can’t do that because the taco is national patrimony!” After some legal wrangling, Bustamante found a way to construct the right legal language as a copyrighted art work ( not actionable in court, otherwise she would be able to sue 100 million Mexicans, as well as the whole world) that would effectively allow her to claim that she had patented the food item. “So, whenever you eat a taco”, Bustamante said on that occasion, “keep in mind that I am giving you permission to enjoy my invention.”

I tried to get clarification on the legal aspects of patents, so I turned to Mike Smith, who is a patent law attorney. While his practice is largely external to the art world, he is married to the intrepid curator Jess Van Nostrand, and occasionally has done patent work for artists, as was the case of the art duo Jennifer and Kevin McCoy, who sought a patent for their jumpstart company named Monegraph, which facilitates the minting, selling, and distributing of NFTS.

Smith gave me a crash course on patent law, explaining the issues that only were vaguely clear to me initially. Methods to make things, Smith clarifies, are indeed patentable, but these need to rise above what would be considered a mere technical contribution to an existing invention. “One of the key thresholds is what we call ‘obviousness’”, he said, meaning that the idea has to go beyond what already exists. An example involves whether a patent seeks to exploit “traditional knowledge”, Smith explains, for example when “companies come in and take the traditional knowledge of how you make bread in, say, Cameroon, and [seek to] patent inventions that at least have some origination from traditional practices from that country.” An interesting detail that I didn’t think about and which Smith pointed out was that in order to obtain a patent you need to make it public, thus opening the door to potential illegal imitations, which is why in some cases it is kept instead as a trade secret (like the formula of Coca-Cola). This is also the source of one of the greatest patent wars of recent memory, which is Apple vs. Samsung over the patent of the iPhone.

Which brought me to the question: can one patent useless things? Like for example, the famous useless Japanese inventions, or chindogu? The answer is, probably yes. According to Smith, a patent can’t violate scientific principles (e.g. you can’t patent time-travel) but it has to work to do something, even if poorly. Chindogu inventions, while absurd, do. function, thus satisfying their absurd purpose.

All of which made me think that socially engaged art projects can be perfectly patentable, Arte Útil in the terms of my friend Tania Bruguera. I will have to think more about that. In the meantime, I will look into seeing if we can get a patent for that tortilla warmer one day, and I will propose an invention to Ellen’s project: a tortilla machine-like pedagogical method for generating fresh new inventors.

No hay comentarios.:

Publicar un comentario